The Myth is an

imaginary narration of fabulous and magic genre, telling the exceptional

deeds of heroes and supernatural beings. It gives a fanciful and an irrational

explanation to the many events and the natural phenomena that man was not able

to explain, as for example the origin of

mankind, the existence of life and of the universe, the prevalence of death

over life, the eternal contrast between good and evil.

In this sense the

myth is also the idealization of an event or of a character, so important to attract and fascinate

in a deep and irrational way the popular collective imaginary.

The world “myth”

derives from the Greek language and means exactly story, legend.

The myths

originally were handed down from generation to generation orally by word of

mouth, thanks to men responsible for this function: wizards, priest, cantors, bards.

Only in a second

moment some poets wrote down the Myths, even if this didn’t prevent their

popular oral transmission.

Since the most

ancient times all the people have felt the necessity of relating their own vision of life and of the

world: the Myths express the fundamental conceptions of each society, the experience of the

people, they represent the soul of a

community, in this sense, they are a precious and irreplaceable cultural

heritage of any people or social group, as they reveal their way of

living, their uses, the costumes, the

religious beliefs. Every people on the Earth, as primitive and culturally simple can

be, have produced their myths, relating

to the differences of time and place, social and economical organization.

At the same time, even if they belong

to people completely different among one

another, the myths present some

identical characteristics as the essence

of the human nature is almost equal; therefore also the myths belonging to

people living in primitive state as the Boscimans or

the Bantus, have something in common with those read in the pages of people that have attained, in their historic

path an elevated degree of civilization as the Egyptians, the Greeks and the

Romans.

The Myths are an example of the culture and

civilization reached by each

people: varying from the

simplest and unsophisticated narration to the most elaborated expressions,

being, always the symbol of the prestige of

advanced and complex forms of civilization.The

grandeur of the myths is entrusted to the written codification given by the

greatest authors of the past. For the Latin world the encyclopaedic references were the

Latin writers Ovid and Virgil, that represent

the most authoritative and reliable source, from which all the other

writers drew inspiration. Ovid’s “Metamorphosi” have been an

important reference point for all the Middle Ages. Their tales and stories have the precise

objective to give an explanation to reality, to what man can’t explain, to

what somehow, concerns man and his

necessities.

Myths, legends and tradition in Sicily

Since ancient times it has

been the scenery of Myths

and legends that have intermingled with its religious roots, many

of them have much to do with water as the symbol of life, of agriculture, of

what was really important and essential to the insular life.

This land of culture and

kindness is open to all his visitors with the incantation of his eternal

beauty, with the majesty of his history, the splendour of his art and the

magnificence of his monuments, and above all, with the hospitality of this

people.

Strong is its tradition of

ancient myths linked to water, some of them will be presented as an example of

our greatest cultural heritage.

Aretusa was one of

Artemis’s nymphs who lived in Acaia , in

She was considered

a very beautiful nymph but she blushed of her natural beauty, feeling this as a

fault. Ovid and Virgil narrate her story:

One day returning

rather tired from the forest of “Stinfalo” , she stopped at the shore of a little river to refresh

herself. Undressed she plunged into the fresh and clean water.

Alfeo, the river in

which she was “freshening”, noticed her beauty and assuming human features

started to woo her to obtain her love.

Aretusa escaped running as

fast as she could till she was exhausted. Till Diana moved by her fear decided

to cover her with a cloud , hiding her from Alfeo’s sight.But Alfeo didn’t lose his heart and continued to look for the

loved Aretusa. The nymph started weeping tillshe

became a river.

Alfeo recognized in the

brillant water the loved nymph left his human

appearance and returned to be a river to be able to mix his waters with hers.

Eventually Artemide made a tear into the ground that

permitted to Aretusa to sink in a dark cave till she

reached Ortigia near Siracusa

, in

Historical references

Ovid : Metamorphosis

5, 572

Virgil : Eneid 3, 1092-1097

“To

be between the devil and the deep blue sea”

The legend

narrates that Glauco fell desperately in love with Scylla,

a beautiful nymph, Crateide’s (or Ecate’s)

and Forco’s daughter, known as she refused all her

pretenders. One day, Glauco, god of the sea, saw her,

as she was wandering about the beaches near

Opposite Scylla on

the other side of the Straits, there lived another monster Carybdis,

Poseidone’s and Gea’s son.

He sucked and spat the sea water three times a day, swallowing whatever he met.

It is told that Ulysses who crossed two times the

Historical references:

- Apollonio Rodio, IV 784-90, 825-32,922-23, narrates about the Argonauts

who

avoided Scylla and Carybdis’s danger with the help of Era and Teti.

- Ovid Metamorphosis XIII 898, XIV 74

- Homer Odyssey XII 308

- Virgil Eneid III

410-32 686-689

- Licofrone, Cfr. Alex 44-48

649-50

Ancient conflicts and contemporary issues:

The Bridge between Scylla

and Carybdis.

What environmental Impact?

The Bridge: an open question. Pro and

versus

The legend

narrates that Aci, the son of Fauno

and the nymph Simete, fell passionately in love with the

nymph Galatea, who reciprocated his love. Unluckly

she was also the object of desire of the Cyclops Polifemo,

who didn’t accept to be refused. Beyond description was his wrath when he saw

Galatea in the forest embraced with Aci tenderly,

furious and blinded with rage he didn’t hesitate to hit the rival with a huge

rock, wounding him to death.

The poor Galatea

started weeping so much that the Gods, moved by her grief, turned Aci’s blood into water, originating the river Aci, near

Another version tells that Galatea’s tears

turned into a river and Aci became its God and

finally another version tells that Galatea eventually accepted Polifemo’s love.

Indeed in

Historical

references:

- Ovid Metamorphosis XII

- Petrarca Trionfo d’amore II,169-171

There is a

language understood by everybody which neither evolves nor dies

, as it is atemporal: a language that tells us

our past, delivering to the eternity, to the collective imaginary, places and

heroes, the divinity and the humanity through which man doesn’t feel

immortality denied and comes out of the darkness of ignorance; through the

experience of heroes whom he identifies

himself with, of terrible and gloomy

places, that he knows he wouldn’t ever meet in his life.

The Acheron plays

a very important role in the conception of traditional Myth.

It is an infernal

river that runs in

It was Omer that

mentions it for the first time in the Odyssey, it is dark and menacing, only

the damned souls can cross it to descend in the dreadful hell “ Ad infera” but on condition that

the human body that had hosted them

during their life had had an honourable burial. It is one of the river of the

Therefore Priamo implores the heroic Achilles in the Iliad to give back Hector’s body to give him a fair burial .

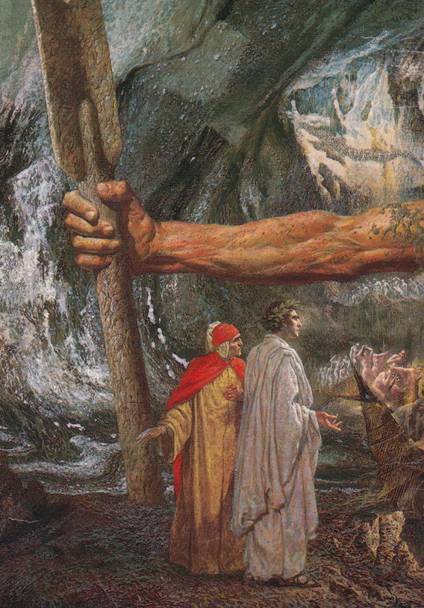

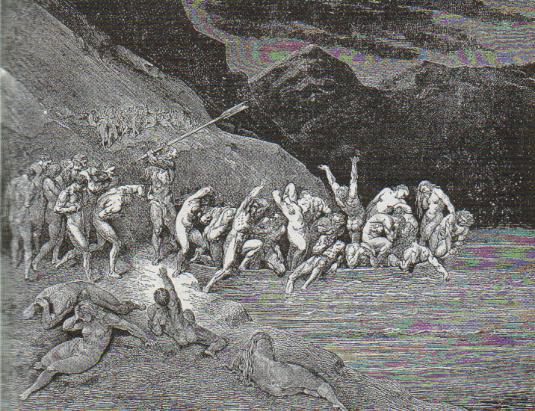

Dante in his

“Inferno” recalls it to our memory accompanied and made more lugubrious through the hellish figure of his helmsman Charon ”Caron demonio dagli occhi di

bragia…….” yet “la tema si volge in desio”

the damned souls throng on its banks, pushing their way , they all want to

cross the Acheron, husband of the Gorgon Gorgira,

father of the howl Ascalafo.

How does modern

man read the myth of the Acheron today?

It is the

extension of the mournful course of the human existence, l’ “Obulum” that we pay to cross it, the price due to our wish

of knowledge, to poetry that has eternized this meaningless course of river,

turning it into a atemporal

myth.

The Divina

Commedia is one of the greatest poems of the Middle

Ages. The work is divided into three parts (cantiche):

Inferno, Purgatory and

Dante conceives Hell as a

great funnel-shaped cave lying below the northern hemisphere with its bottom

point at the earth’s centre where Lucifer lives. Around this great circular

depression runs a series of ledges, each of which Dante calls a Circle. Each

circle is assigned to the punishment of one category of sin, which becomes worser as the abyss gets deeper. The circles are populated

with monstruous mythological creatures which guard

the place they are assigned to. Dante depicted this imaginary place according

to the mentality of his time: a dark world with no stars, where there is only

weeping, pain and cries: a gloomy, deep atmosphere at times violently swept by

strong winds whose blows are as feroucious as the

roar of a stormy sea or as the heavy cold rains which constantly shake the

damned souls. Thus Dante describes the Gate of Hell, a blank place where

everything is wrapped in heavy shadows.

Allegorical

meaning of the poem

Dante imagines to be the protagonist of an extraordinary journey that

lasted about one week and which took him, during the Spring of 1300, through

the three realms of the afterlife: Hell, Purgatory and

This journey should not be

looked upon as a mere narrative description of the afterlife, but must be

interpreted following its deep, allegorical meaning: Dante represents mankind

who experiences a profound spiritual crises which one can overcome only if

aided by human reason (represented by Virgil’s figure) and faith.

The guardians of Hell

Dante’s poem thrills the modern

reader’s imagination by the use of various mythological figures, monsters which

are to be found at the entrance of each circle. Among these:

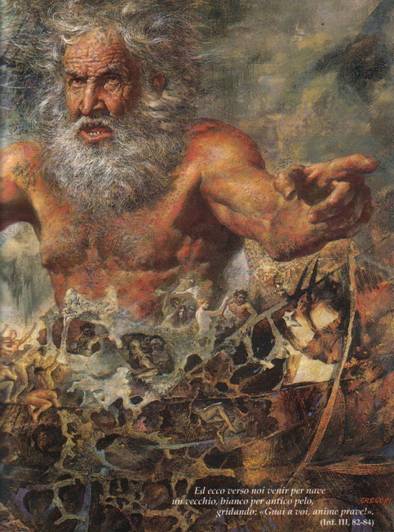

Charon, the ferryman who carries

the dead souls across the Acheron, the first of

the rivers of Hell, over to punishment. He is not a wise man; he is

old and has a thick beard as white as his hair; with eyes of flames he

threatens and frightens the damned souls.

Minos is the dread

monster, judge of the damned who horrendously growls like a dog while assigning

to each soul its eternal torment. After hearing each admission of sin, he

decides to which circle sinners must go. Then his tail twists around him

forming as many circles as those the damned soul must descend.

Cerberus is the ravenous

three-headed dog of Hell who barks against the sinners that lie in the slush.

He has eyes of fire, a large belly and with his claws and teeth rips and tears

the souls of the third circle: the Gluttons. a

hoarders’ sins.

Each of these monsters tries

to stop Dante from descending through the circles of Hell, but Virgil silences

them and so the poets move on.

Ed elli a me: << Le cose ti fier conte,

quando noi fermerem li nostri

passi

su la trista riviera d’Acheronte >>.

Allor con li occhi vergognosi e

bassi,

temendo no ‘l mio dir li fosse

grave,

infino al fiume del parlar mi

trassi.

Ed ecco verso noi venir per nave

Un vecchio, bianco per antico

pelo,

gridando: << Guai a voi,

anime prave!

Non isperate mai veder lo cielo:

i’vegno per menarvi a l’altra

riva

ne le tenebre etterne, in caldo

e’n gelo.

E tu che se’ costì, anima

viva,

pàrtiti da cotesti che

son morti >>.

Ma poi che vide ch’io non mi

partiva,

disse: << Per altra via,

per altriporti

verrai a piaggia, non qui, per

passare:

più lieve legno convien

che ti porti>>.

E ‘l duca lui: << Caron,

non ti crucciare:

vuolsi così colà

dove si puote

ciò che si vuole, e

più non dimandare>>.

(Inferno, Canto II, Dante Alighieri, La

Divina Commedia)